The first pocket knives in history were used as early as Roman antiquity, but these did not yet have locking mechanisms and were held open solely by friction on the inside of the handle halves. Today, these simple knives are known by the English term friction folder. To make pocket knives safer to use, numerous mechanisms were developed over the centuries to lock the unfolded blades in place. We would like to briefly explain the function of the most common constructions used today.

This blade locking mechanism was invented by Chris Reeve, who originally coined the term Integral Lock for it. The mechanism is based on a locking spring that is part of the handle frame, which is usually made of titanium or aluminum. The locking spring is a bolt cut longitudinally into one of the two halves of the handle, which is pretensioned. When the blade is unfolded, this latch snaps under the blade root and locks it in place. To retract the blade, the locking spring is pushed to the side. When closed, a small ball (detent ball) pressed into the locking spring engages in a tiny depression in the blade root and prevents the blade from opening accidentally. The relatively simple design allows framelock folders to be very low profile. To reduce wear, some manufacturers have taken to mounting a replaceable steel plate at the point of contact of the aluminum or titanium spring with the blade root, which avoids direct friction between the softer materials and the steel blade root. In addition, some Framelock models have over-extension protection: a small washer screwed onto the handle prevents the spring from being pushed too far outward during unlocking. This washer can also take on the function of an additional lock for the locking spring.

The backlock locking mechanism, also called back locking in German, is a proven mechanism whose origins date back to the 19th century. The construction consists of two components: A locking lever is held under tension by a spring anchored at the rear handle end. At the front end, the lever engages a hammer-shaped head in a correspondingly shaped groove in the blade root. To release the lock, the lever is pushed down against the pressure of the spring. Usually, there is a crescent-shaped depression at the rear end of the handle that allows the lever to be pushed down. However, there is also a variant where the pusher is located in the middle of the back of the handle (mid-backlock). Even when the blade is folded, the locking lever presses on an edge of the blade root to prevent accidental opening of the blade. Due to the symmetrical design, backlock folders are suitable for both right-handed and left-handed users.

Around the middle of the 17th century, English cutlers invented the back spring. The spring, mounted between the handle scales, presses on a step-shaped recess in the blade root and in this way inhibits the folding of the blade. This mechanism, known as a slipjoint, is not a locking system in the strictest sense because the blade does not have to be unlocked before the knife is closed. The blade only has to overcome the resistance of the back spring when folding. The spring tension also prevents the blade from accidentally folding out. Slipjoint knives enjoy great popularity, especially in Germany, because they are not subject to a carry ban under current law. However, one disadvantage of this type of pocket knife is that the blade can fold in unintentionally if used carelessly. To make operation safer, some Slipjoint models have a so-called Half Stop: When the blade is closed, it engages at the 90-degree position in a clearly noticeable way, so that the fingers are protected.

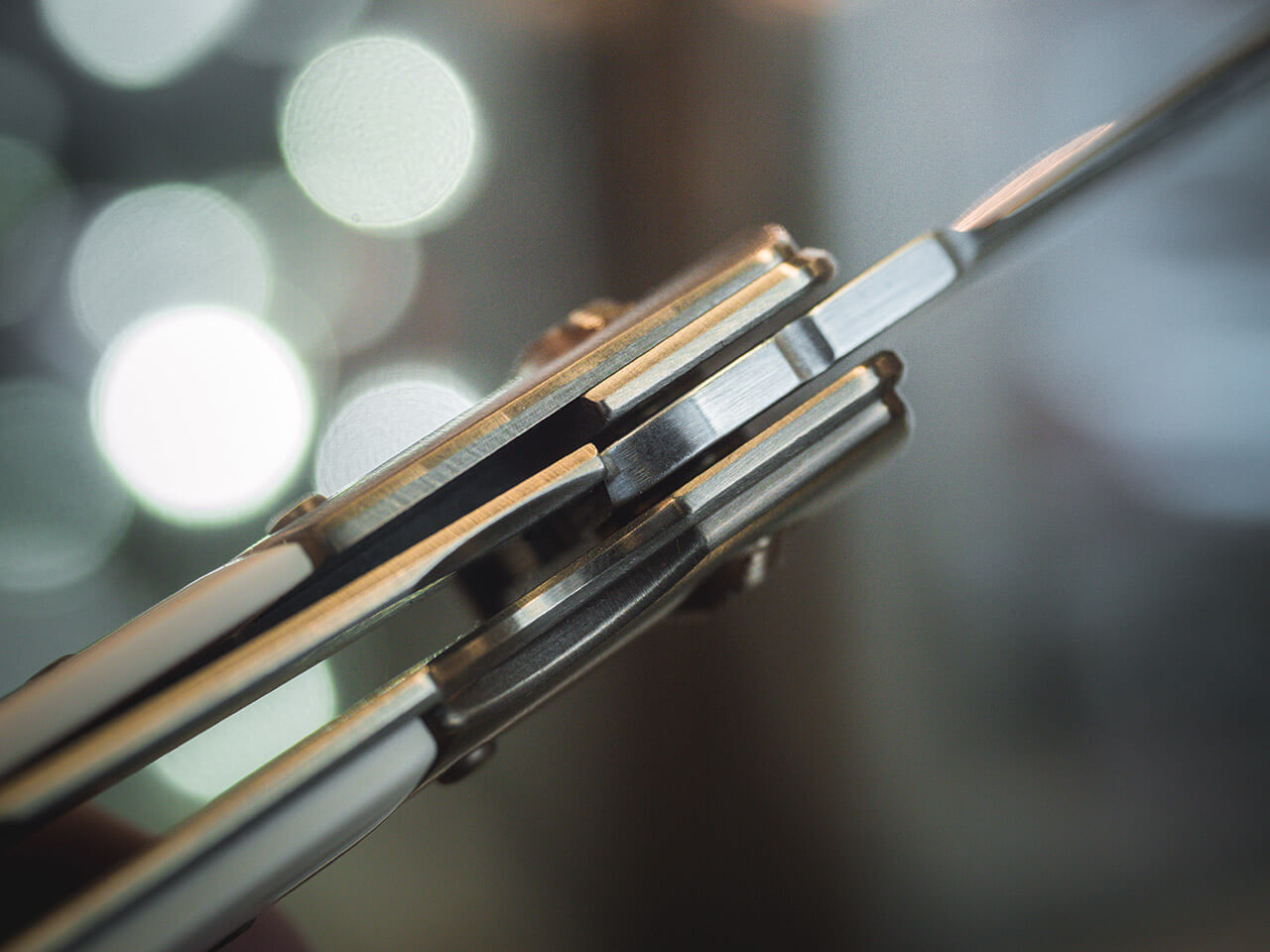

The linerlock mechanism perfected by American knifemaker Michael Walker is often used on pocket knives whose handles are composed of metal plates and handle scales placed on top of them. As with the Framelock, a locking spring ensures that the blade is locked in the open position. In contrast to the frame lock, however, the locking spring is part of the plate and therefore much thinner. In handle designs without sinkers, the spring can also be inserted as a separate component in the handle shell. When the knife is opened, the spring slides under the usually beveled stop of the blade root. When the spring is pushed to the side, the blade can be folded back in. A detent ball holds the closed blade in the handle. Even though the locking spring is usually much thinner than with the Framelock, the Linerlock is a very reliable locking mechanism. On the other hand, one disadvantage of both systems is that they are usually only designed for right-handed operation. Only a few manufacturers offer special left-handed models.

BUTTONLOCK / PUSH BUTTON

The design of the push-button lock, also known as button lock, consists of a locking bolt mounted on a coil spring that can be pressed down through a hole in the handle. When the blade is unfolded, the blade root slides over the widened base of the bolt and pushes it down. The widened base snaps precisely into a corresponding recess in the blade root, locking the blade in place. When the bolt is pressed down using the push button, the smaller diameter part of the bolt releases the blade root. When the blade is folded, the coil spring pushes the bolt into another groove, which is shaped to reliably retain the blade in the handle.